Society of the Nine award to ”My big beautiful hatred. A biography of Victoria Benedictsson”.

Elisabeth Åsbrink is awarded Lotten von Kræmer’s grand prize for non-fiction of SEK 200,000 by Samfundet de Nio. TT 28 September 2022

*

”A magnificent biography… Elisabeth Åsbrink has written a captivating biography of a fascinating fate.” Christian Swalander, Alba

”Throughout, Åsbrink enhances the autobiographical material with tempo, rhythm and temperament: a smell of burnt hair from a curling iron, the sound of tram bells from Kongens Nytorv, a streak of light on a thick carpet. This is how Benedictsson’s sentences rise from the paper and a lived experience enters out of the shadow of the archive. Color rises on the cheeks and the phantom speaks.” Alexandra Borg, DN

”The fact that I believe that I know this history inside and out doesn’t matter, I devour Elisabeth Åsbrink’s book as if I had no idea how it will end.” Ann Lingebrandt, Sydsvenska Dagbladet

”It’s a very moving story that is presented all the way to the end. I’m drawn in and keep wanting to read.” Jimmy Vulovic, Borås Newspaper

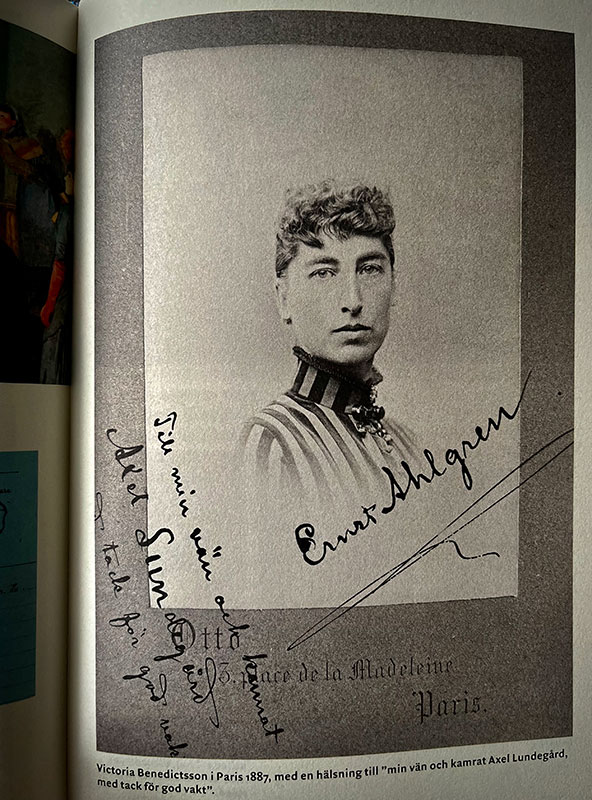

”In this excellent and extensive biography, Åsbrink gives a comprehensive picture of the writer and playwright Victoria Benedictsson (1850-1888), pseudonym Ernst Ahlgren, and her work. […] My big beautiful hatred is an insightful, solid and well-written presentation of a writer’s life that feels astonishingly current. Benedictsson’s courageous efforts to make society more open and equal also appear in a new way.” Inger Littberger Caisou-Rousseau, BTJ no. 15, 2022

Åsbrink […] writes so artistically and vividly. Sometimes it even feels like an Agatha Christie detective story…” Nina Lekander, Expressen

*

”My big beautiful hatred. A biography of Victoria Benedictsson”

by Elisabeth Åsbrink, Polaris 2022

Are women females or humans? Are men masters or slaves? Is marriage a business arrangement, an act of love, or a prison sentence? Should Christian morality or reason prevail?

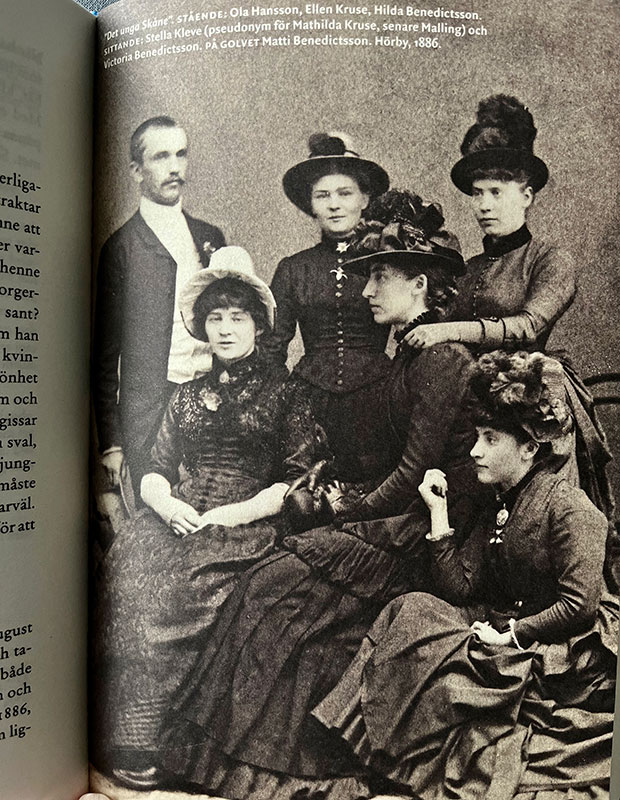

The questions formulated during the second half of the 19th century set Europe ablaze, and it was authors and intellectuals in the Nordic countries who ignited the fuse. At the center was the Danish literary critic Georg Brandes, who in lectures and pamphlets called for doing away with ossified gender patterns, stale bourgeois morality, and inequalities both domestic and societal. He was joined by Henrik Ibsen, August Strindberg, Elisabeth Grundtvig, and Anne-Charlotte Leffler, to name a few.

Amid the upheavals and heat of battle, Victoria Benedictsson emerged like a shooting star in the sky of literary realism. The postmaster’s wife from a peripheral Swedish village made her literary debut at age 33, charging straight into the center of the action under the pen name Ernst Ahlgren. She befriended (or antagonized) all of the era’s key players and her books took on the hottest issues of contemporary debate.

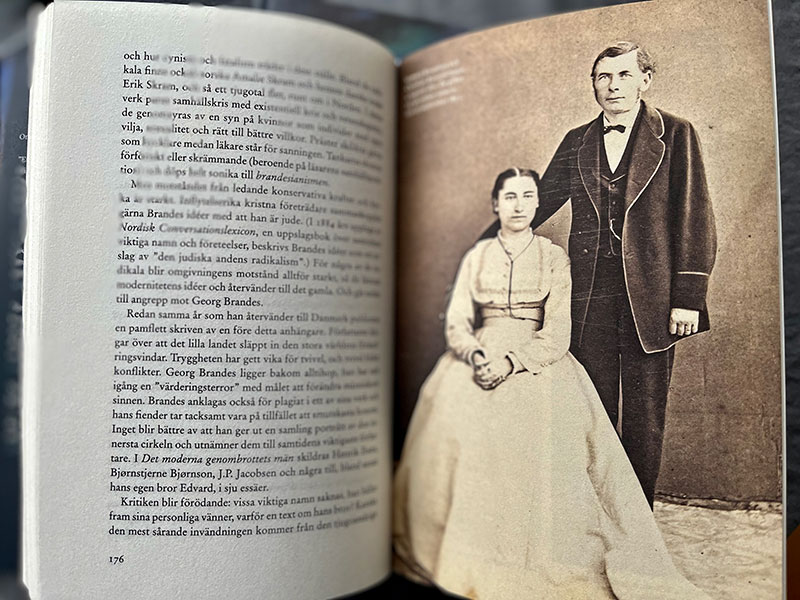

A lanky peasant’s daughter from a farm beyond the highroads, she married a postmaster thirty years her senior, and became stepmother and mother to six children in all. She started educating herself in secret, writing and submitting pieces to newspapers. By acquiring a male pseudonym she began her escape from prescribed femininity––which she regarded as a prison––and took the liberty of critically examining marriage as well as praising it.

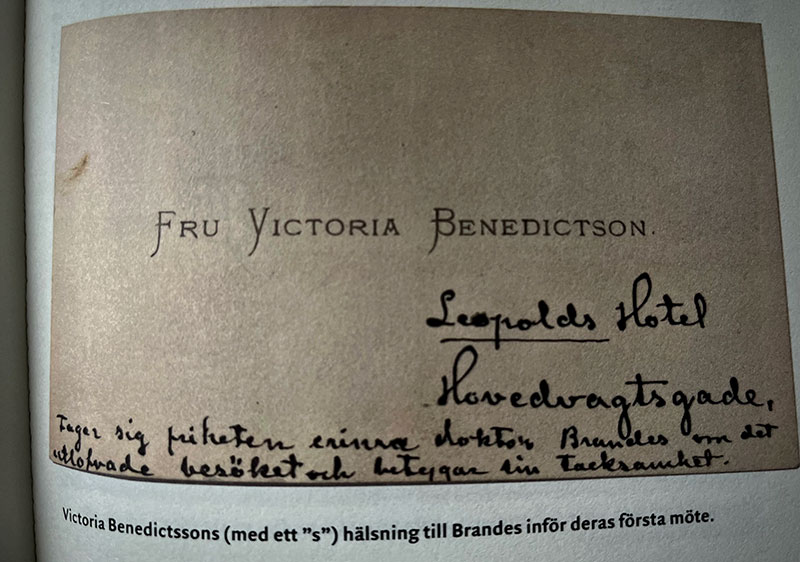

She met the admired Brandes and fell deeply in love with him. She got to know August Strindberg and partied with Ibsen. First admired and then rejected by the feminists of the time, outcast and unwanted at home, she finally expelled herself. It was a short career, really only six years, but incredibly intense. In the end, she took her life with a razor in a Copenhagen hotel.

Three weeks later, August Strindberg finished his play Miss Julie, in which the main character met her demise in the same way. In less than a month, Victoria Benedictsson went from being the main character in her own drama to being exploited in others’.

In her new biography, Elisabeth Åsbrink has carefully retraced Victoria Benedictsson’s steps. She has read letters, diaries, short stories, and novels in order to shed light on the inner landscape of a prodigious figure and a period in which the Nordic countries went from being governed by Christianity to embracing modernity and science.

This is a biography of a thinking woman who tried to shatter the constraints of gender and ended her life in a crescendo of emotions, in a time obsessed with literature, sex, and death.